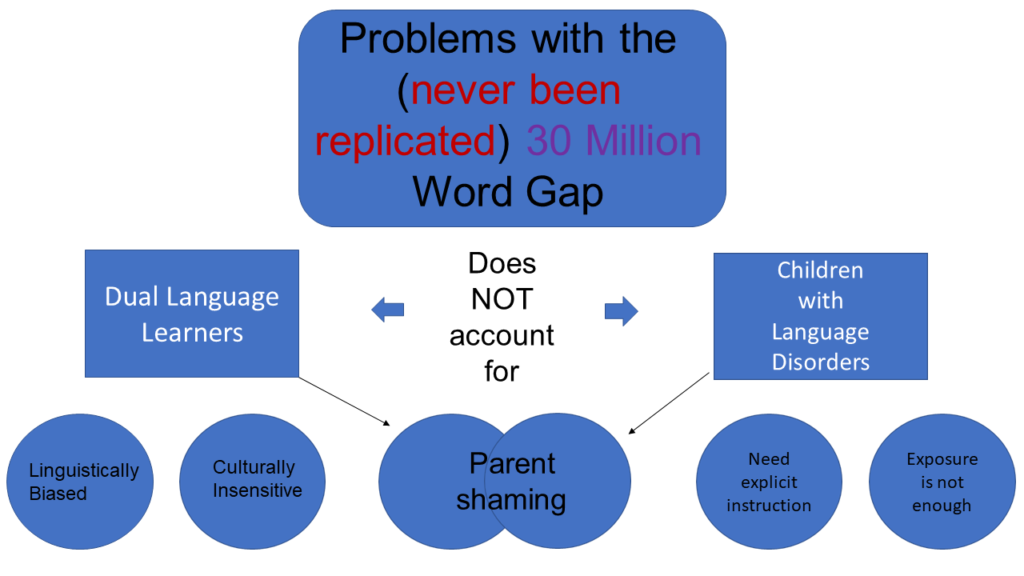

About a year ago, NPR published an excellent article discussing how the 30 million word gap needs reframing. The idea of the word gap started with two developmental psychologists Betty Hart and Todd Risley in the 1960’s. I first learned about the study as an undergraduate student in my speech and language development classes. I remember as a naive student learning that parents who didn’t talk to their children as much caused children to have a depressed vocabulary. I didn’t realize how dangerous this type of lesson was, as not only was the study itself fraught with racial bias, but it essentially “blames” parents when a child has a reduced vocabulary. I was taught this in a class where I was studying to be a speech/language pathologist who would help kids with legit language disorders. Does one see the problem? I was being taught about language disorders and simultaneously was learning about a study that said children have reduced vocabularies because their parents didn’t talk to them.

I only realized after I had a child with a communication disorder, just how judgemental professionals can be. This is in light of me being a white, graduate level speech/language pathologist. I started to realize how well-intentioned studies like the 30 million word gap end up blaming parents instead of doing what they say they intend to do, which is to help close the gap.

Now a new research article has caught fire and is making the rounds. Instead of blaming parents for not talking to their children, it’s blaming parents for not reading to their children. Today I invited two professionals with me to dissect the article and review it from our varying perspectives. I (Laura Smith, Speech/Language Pathologist) will be commenting from the view of monolingual children with Developmental Language Disorders (DLD). Teresa Gillespie (Bilingual Speech-Language Pathologist) will be commenting on the perspective of (culturally and linguistically diverse variables to consider for bilingual speech-language assessment and intervention), and Kara Viesca (Associate Professor of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education) will be commenting from the perspective of multilingual language development. Hello ladies! Thank you so much for being here! I can’t wait to break down this very important topic!

1. What are the positives to a study like this?

Kara: We do know the positive benefits of reading with children and this study appears to be seeking to underscore those benefits and wanting to inspire more reading with children.

Laura: I can’t find any.

Teresa: When I look at the landmark study by Betty Hart and Todd Risley regarding the “word gap,” I remind myself that the purpose of their study was to explore the differences in language development and later academic achievement between children from lower socioeconomic levels and those from higher socioeconomic levels. They sought to understand the causes of these differences. From this perspective, I think that a positive in studies about “word gap,” “talk gap,” or “language gap,” is that researchers continue to search for and explore the reasons for the differences in the language development and educational performance of children from lower versus higher socioeconomic levels.

2. What are the dangers in a study like this?

Kara: We live in a very diverse society with a lot of complexity in the differences across home life based on cultural and linguistic practices. A study like this is can be used to promote the cultural and linguistic norms of one cultural group (White, middle-class, monolingual English speaking) over those of another and in the end blame parents and families for students performing in particular ways in school.

Laura: As a Speech/Language Pathologist (SLP) and mother to a child with a language disorder, simply reading a book will not be enough to ever acquire the vocabulary or language naturally in kids with DLD. These children require explicit and direct instruction and engagement with a book. I get concerned when I see studies like this because SLP’s are quick to spread the “positive” message on the benefits of reading and how many more words a child is exposed to when being read to; however, this can flirt with the dangerous idea that children who continue to struggle with language or have a low vocabulary have it because they were not read to enough. Instead, there is a possibility that the child has a legitimate language disorder.

Teresa: As a Bilingual Spanish/English-speaking Speech-Language Pathologist, I received specialized training on the different culturally and linguistically diverse factors to consider in bilingual speech-language assessment and intervention practices, including during the review of research study results that may affect those practices. When I look at the results of the original study by Hart and Risley, I ask myself how they apply to the population of individuals whom I serve. I work with bilingual Spanish/English-speaking Kindergarten – 12th grade students with identified speech-language difficulties in both Spanish and English. I can’t apply the results of the Hart and Risley study to the population I serve because they did not include bilingual Spanish/English-speaking individuals in their study. In fact, to my knowledge, there currently aren’t any published “word gap” research studies in the United States that include bilingual speakers of English and languages other than English. It would be inappropriate for me to apply the results of any “word gap” study to my bilingual speech-language pathology practices that consider vocabulary and language development in only the English language, which is a second, and sometimes a third, language for the population I serve. Any professionals, such as General Classroom Teachers, Special Education Teachers, Reading Interventionists, Speech-Language Pathologists, etc., who work with bilingual speakers of English and languages other than English need to consider the vocabulary and language development in English as well as the languages other than English in order for their services or assessment/intervention practices to be sound. This is true for not only bilingual speakers, but also for trilingual and multilingual speakers. The results of numerous research studies in the professional fields of psychology, speech-language pathology, linguistics, etc., indicate that considering the vocabulary and language development in only the English language for bilingual speakers underestimates their overall language abilities. When the vocabulary and language development of bilingual speakers focuses only on the English language, then the application of the results of the “word gap” studies becomes about English language proficiency and not true language abilities.

3. What biases are present?

Kara: We have to be honest about the reality that biases are always present in all studies as well as in our educational practices and policies. One of the typical biases we have is based on what we consider “normal” — this is how we create and perpetuate ideas about gaps. If we consider it “normal” for children to have the linguistic practices of White, middle-class, monolingual English speaking families, than students who come from different backgrounds will often appear to have a “gap.” If the norm was altered to mirror the linguistic and cultural practices of students from Latinx, bilingual English/Spanish families from the working class, then the students who currently appear to not have a gap, would appear to have one. In education around language, we hold English monolingualism and White middle-class culture as the norm for which all students should strive–a clear, pervasive and ongoing bias that continually positions certain students to have “gaps.” This study holds this same bias, assuming a particular norm is what all students and families should be aiming for that doesn’t account for legitimate, helpful and valuable cultural and linguistic variations that occur across families and cultural groups.

Laura: In terms of children with language/learning disabilities, they are not even addressed in the study. The article didn’t prove anything except to show that kids who are read to are exposed to more vocabulary and then cite other (biased) studies showing how exposure to more vocabulary is linked to the later vocabulary trajectories.

It’s important to mention studies showing how children with DLD have difficulty picking up vocabulary implicitly and need explicit instruction, before making conclusions that their vocabulary exposure contributed to their acquisition and retention.

Teresa: One of the biases is that children from lower socioeconomic levels come from homes where they receive less vocabulary and language development experience. This is not the case. The results of a recent study by Douglas Sperry, Linda Sperry, and Peggy Miller indicated that children with fewer vocabulary words and low language development skills did not all come from homes with lower socioeconomic levels or less vocabulary and language development experience. There was a wide variation in home language experience among all socioeconomic levels.

Another bias is that children have the same kind of language enrichment experience at home regardless of cultural and linguistic background. This is not true. Different languages and cultures provide different language enrichment experiences at home. Even different dialects and subcultures provide different language enrichment experiences at home. There can be oral language experiences that do not include parents reading books to their children. Instead, the parents tell and retell folktales or sing ballads that share the knowledge, ideas, and beliefs of their culture to their children. In the absence of factors that negatively impact language development, these children do not experience any less academic achievement than those children whose parents read to them from books. There can be language experiences that do not include parents providing comments or asking questions about what their children are doing, how they are doing it, etc. Again, in the absence of factors that negatively impact language development, these children do not experience any less academic achievement than those children whose parents provided comments or asked questions about their children’s various activities.

A third bias is that children who have adequate vocabulary skills and “typical” language development in English will experience academic achievement. Again, this is not the case. There are children who exhibit adequate vocabulary skills and “typical” language development in English who do not experience academic achievement. Also, provided with the appropriate supports, both in the home and school environments, children exposed to a language or languages other than English, as well as English, can and do experience academic achievement. To focus on vocabulary and language development in only the English language for bilingual, trilingual, or multilingual speakers is to diminish the benefits of bilingualism/multilingualism, and possibly cause members of other cultures to feel less important or respected.

4. What suggestions do you have for supporting children’s linguistic development?

Kara: My area of focus is in multilingual language development, so from that perspective I suggest doing as much as possible with language, particularly in authentic ways for meaningful communicative purposes. Children who live multilingual lives have developed strong communication abilities that respond to the communities and people they seek to communicate with. Too often at school, we don’t acknowledge this and focus on “gaps.” I’ve even sat at the table with a state commissioner of education who said, “These kids are showing up to school with no language.” I quickly called him out on this statement, because the kids he was talking about (and why I was at the table) are bilingual/multilingual students who, barring disabilities, have expansive language skills. They just might not be the language skills we have set as the norm or value in our schooling practices. In fact, this practice of constantly comparing multilingual students to their monolingual peers and identifying “gaps” creates an ongoing context of deficit thinking towards multilingual students. I resist focusing on gaps to the extent we do in education as I think we get too bogged down in “needs” and “gaps” and don’t work with students from a position of their strengths and learning assets. A child who did not have the traditional White, middle-class, monolingual English speaking literacy experience before they came to Kindergarten did have a lot of important linguistic and cultural experiences that offer strengths to that learner in school. We just have to learn to see those strengths, embrace them and work with students to grow them.

Laura: From the perspective of children with DLD, linguistic development is enhanced through therapy and direct and explicit instruction. No amount of just talking to or reading to the child with DLD is going to help them overcome a language disorder. That doesn’t mean talking to and reading to children with language disorders doesn’t “help” but it’s not the entire piece of the puzzle. Parents and professionals can change the way in which they read and talk to the child and employ strategies that help the child with DLD process and use language effectively, but this is done through the skilled care and recommendations by the speech/language pathologist. In sum SPEECH THERAPY is the most effective way to treat language disorders and build vocabulary.

Teresa: For me, the most important suggestion for professionals in the United States who work to increase the vocabulary and language development of bilingual/multilingual speakers is to encourage the continued understanding and use of the native or home language(s) while fostering the acquisition of English. English language development can successfully occur in an “additive bilingual” environment. An “additive bilingual” environment not only promotes the continued learning of the native or home language(s) while learning English, but also preserves the cultural identity or identities of the speaker, which leads to a feeling of being valued.

The most important suggestions for parents of bilingual/multilingual speakers of English and a language or languages other than English are to maintain the native language(s) in the home environment, and become as familiar as possible with the academic expectations for each grade that your child attends. It is also important to become as familiar as possible with the academic resources available to your child at the school and district levels. These resources promote student academic achievement, and are helpful to parents who may not feel confident supporting their child’s academic learning in the home environment.

Thank you BOTH SO MUCH! I hope we have provided alternative perspectives that will get professionals thinking instead of blindly re-sharing a catchy research article. In summary, I think we all agree the 30 million word gap is inflated, has never been replicated, is inherently biased, and beyond the catchy headline doesn’t hold a lot of substance or provide any meaningful information. So please everyone, “Mind the Gap” and let’s not fall in feet first.

Kara Mitchell Viesca, PhD is an Associate Professor of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education at the University of Nebraska Lincoln. Her scholarship focuses on advancing the policy and practice of educator development for teachers, particularly of multilingual learners. She has been awarded $4.6 million in federal funding to support quality teacher learning initiatives for teachers of multilingual students and has published her research in a variety of academic journals. For more information, please visit: https://cehs.unl.edu/tlte/faculty/kara-viesca/

Teresa Rizzi Gillespie, M.S., C.C.C., CBIS, is a Certified, Bilingual Speech-Language Pathologist and a Certified Brain Injury Specialist. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree in Speech Pathology and Spanish from the University of Denver. Teresa received her Master of Science degree from Vanderbilt University, Department of Otolaryngology and Hearing and Speech Sciences. She is currently pursuing Advanced Certification in Bilingual Speech-Language Pathology through the Bilingual Speech-Language Pathology Extension Institute, Teachers College, Columbia University. Teresa has been providing speech-language services to Kindergarten – 12th grade students in the largest public school district in Colorado since 2002. Prior to working in the public schools, she worked at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Rose Medical Center, and in private practice. Teresa has presented English Language Learners with Exceptional Needs (ELLEN) Project trainings through the Colorado Department of Education. She has been a guest lecturer in the Graduate School of Professional Psychology at the University of Denver, Latinx Psychology Specialty, and has served as a Consultant for an online second language acquisition class offered by the same program. Teresa is passionate about meeting the speech-language needs of Dual Language Learners, and consistently advocates for the appropriate assessment and identification of language difference versus language disorder.

Laura Smith, M.A. CCC-SLP is a 2014 graduate of Apraxia Kids Boot Camp, has completed the PROMPT Level 1 training, and the Kaufman Speech to Language Protocol (K-SLP). She has lectured throughout the United States on CAS and related issues. Laura is committed to raising and spreading CAS awareness following her own daughter’s diagnosis of CAS and dyspraxia. She is the apraxia walk coordinator for Denver, and writes for various publications including the ASHA wire blog, The Mighty, and on a website she manages slpmommyofapraxia.com. In 2016, Laura was awarded ASHA’s media award for garnering national media attention around apraxia detailing her encounter with UFC fighter Ronda Rousey, and also received ASHA’s ACE award for her continuing education, specifically in the area of childhood motor speech disorders. Currently, Laura is a practicing SLP specializing in apraxia at her clinic A Mile High Speech Therapy in Aurora, Colorado.