Disabilities, extraordinary abilities, and lessons in neurodiversity

Neurodiversity and learning disability were never in my vocabulary before I had my daughter.

I had never been exposed to learning disabilities of any kind really, and I had no idea the extraordinary gifts those who are neurodiverse had to offer this world.

No, when I was in second grade, I was in my egocentric world and our teacher had us write “a book.” It was a short story and we were to write on the typical school paper that has a box at the top to draw an illustration and then lines at the bottom to write the story. Writing was always my thing. Art….was……not. I usually skipped the picture and went straight to writing. In my defense though, I never technically had an art teacher. However, even if I had, I’m sure I would have still been that defiant snotty little girl who turned up her nose at art.

During one edit, the teacher told me the book was great but I needed illustrations. I argued with her. Her job wasn’t to teach me how to draw, her job was to teach me how to write. Drawing was for the kids who didn’t know how to write and I knew how, so what did it matter anymore? Did I mention I also went to a Catholic school, so I was marked down automatically for being sassy? I never pulled that again, but it didn’t stop me from internally rebelling against drawing.

“When will I EVER need to know how to draw as an adult?” I indignantly exclaimed to my mom.

My Catholic school teacher had the last laugh though when I became a speech/language pathologist and discovered I needed to know something I didn’t know how to do. You guessed it. Draw.

“What is that? Is that a dinosaur?” one kid would ask of my drawing of a horse.

“That’s supposed to be a bird?” another asked of my drawing of an airplane.

Yes friends. That sassy, know it all second grade girl started wishing she had paid more attention to art.

Fast forward 30 years and I have a little past second grade daughter myself. She has a laundry list of learning disabilities, many stemming from an etiology in motor planning and cerebral palsy. Everything for Ashlynn seems hard. She has had to fight and claw her way to learn anything through hours and hours of therapy. I’m not kidding. In Elementary school, she started coming home with art pieces from art class that were nothing short of amazing. They were so amazing, it was sadly hard for me to believe that she did them without help. However, her art teacher maintained she taught all the kids in a very structured way, giving them multiple opportunities for practice (think motor planning) before completing the final piece. This was Ashlynn’s best one from last year.

Despite this, Ashlynn had never demonstrated to me independently she could draw even remotely close to this on her own.

That was, until tonight.

“Mommy, do you know how to draw a fox?” Ashlynn asked me tonight at dinner.

“Oh baby, I don’t really know how to draw much of anything,” I answered while my husband snorted his drink out his nose in laughter before adding,

“That much is true! Mommy is not an artist.”

I shot him an evil glare but unfortunately there was no denying the truth.

“Can I teach you how mommy? I learned how to draw a fox in art?” Ashlynn offered.

I agreed and after dinner she had gathered paper and coloring utencils and set to work. I really wasn’t sure what to expect.

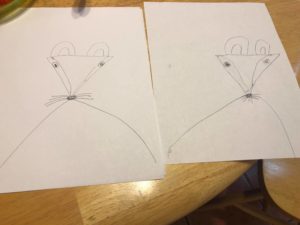

“Put your fist in the middle of the paper like this, and now draw a line across the top,” she instructed.

I complied.

“Now connect this line to this line and see? We made an upside-down pizza,” Ashlynn continued.

I looked at the perfect triangle and my mind raced back to three days earlier at OT where the therapist told me Ashlynn’s hardest shape to draw is a triangle because of the diagnal lines. I stared incredulously again at Ashlynn’s perfect triangle.

“Mom! Are you paying attention?”

She then took me in precise detail through the rest of the picture.

I was impressed by this.

“You are such a great teacher Ashlynn,” I said.

“I know mommy because I want to be a teacher you know that. A teacher and a dog walker because that’s my deal.”

I smiled. She just produced a compound complex sentence. This girl with apraxia and a language disorder just said that.

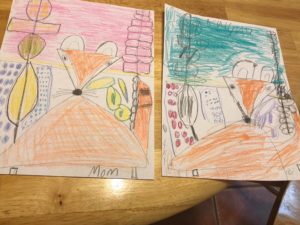

Next was the colors.

I fought back tears. This was incredible. I watched her color the page with her wrist fluidly and precisely moving back and forth and my mind flashed back to when her OT told me that until she is able to isolate her wrist from her arm, she would always have trouble coloring within the lines. I marveled at her wrist now. Isn’t that crazy? What mom would marvel at their child’s wrist and control unless they had witnessed how hard that skill was to master.

Next was texturing and drawing the trees.

She used these terms I had never heard like “we have to jump and bump.” I followed along dutifully. At the end of her lesson I praised her. It was incredible.

“But Mommy, we aren’t done!” she said as she got out two new blank pieces of paper.

She told me we had to write about them.

Write? Like actually write? This girl with motor planning, dyslexia, and dysgraphia now wanted to write about the fox? She began writing but immediately messed up her spelling. As she peered over at my page that she had dictated, she decided to just copy my sentence. I watched her form the letters as she had been taught and practiced throughout her years of OT and copy my sentence. There was a time, she couldn’t even copy her name, I thought to myself.

“Sorry, mommy, ” she said, “I can’t write really good yet.”

I responded, “That’s okay, because I can’t draw very well.”

“But I can teach you!” she said happily.

With tears in my eyes I told her,

“If you teach me how to draw, I’ll teach you how to write.”

“DEAL!” was her enthusiastic response.

So that’s the deal.

Thirty years later my art teacher was a 9 year old girl with cerebral palsy, severe motor planning deficits and a laundry list of learning disabilities whose greatest wish in the world is to be a teacher. Little does she know, she already is.